News & Notes

Redefining “programming” (6 Ps of Experience Design)

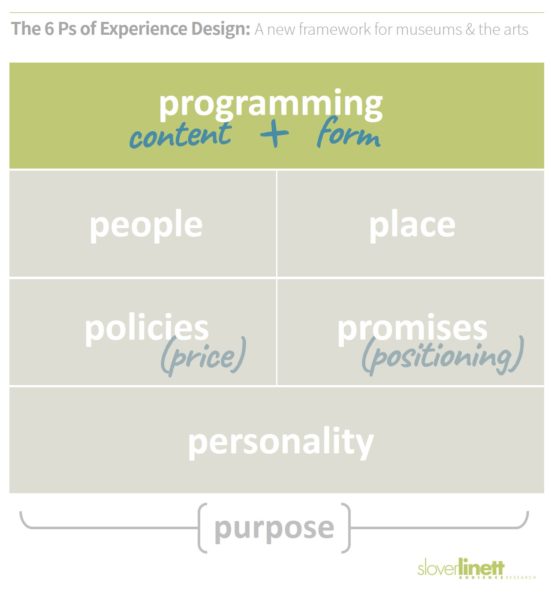

This is the third in a series of posts about our new framework for cultural engagement, The 6 Ps of Experience Design. You may want to read the introduction and overview before continuing here.

- Introduction

- Overview of the framework

- Programming [this post]

- People

- Place

The most obvious P in the framework is the what: what’s on offer. In other words, programming.

But from the audience member’s point of view, the program isn’t just the work being performed on the stage or exhibited on the walls. It’s also the how: how that work is presented, how we’re meant to engage with or participate in it, whether and how it’s mediated by people or technology, and so on.

But from the audience member’s point of view, the program isn’t just the work being performed on the stage or exhibited on the walls. It’s also the how: how that work is presented, how we’re meant to engage with or participate in it, whether and how it’s mediated by people or technology, and so on.

In other words, it’s not just the content, it’s also the form.

As I asked in an earlier post arguing for this dualistic view of programming, can you imagine totally distinct “programs” with exactly the same content?

If you work at a museum, picture the same artworks, maybe even hung in the same sequence with some of the same interpretive facts and framings. But in one case the exhibition is fixed and passive, while in another it’s participatory and evolving. In one case it’s serious, in another irreverent and funny. Designed for solo experiences, vs. for social ones. Unmediated and contemplative vs. technological and multisensory. White-cube vs. immersive or theatrical…

Or, if you work at a symphony, picture the same pieces played at the same level of quality, but vary all those other “form” attributes. (You may need to mentally dismantle your concert hall, not to mention your contract with the musicians union.)

Yet many arts leaders and museum professionals still think of “programming” as synonymous with selecting the repertoire or works, along with casting (in theater), choosing soloists, etc. Could that be because they’re assuming — which is to say, ignoring — the “form” side of the equation? When we already “know” what an art exhibition or classical concert is and how it works, we don’t think much about the conventions of presentation and participation. That’s a shame, because it prevents us from innovating in ways that might bring wider, larger audiences into the fold for the same “content.”

As with every other P in the experience-design framework, we need to strategically and creatively leverage both content and form to create programming that sparks real engagement, meets needs, creates change, and brings people together.

That’s also something to consider when we talk about decolonizing our cultural organizations. If we focus largely on the what and the who, as many museums, theaters and dance companies have done, we may be unintentionally leaving in place the deeper barriers to equity and diversity — barriers that are more about the how of engagement and participation. As I wrote in that earlier piece, it’s vital to expand the artists and artworks we collect, exhibit, and perform. But it’s probably not enough:

Representation onstage or on the wall is a necessary, not a sufficient condition for relevance. We also need to decolonize the forms in which culture is produced and consumed. We need to get more representative and inclusive in our experience design.

All of which brings us to the second P in the framework, the people who create, staff, and participate in cultural experiences. Read the next post in the series…

Photo: Lincoln Center’s beloved Midsummer Night Swing program in action.