News & Notes

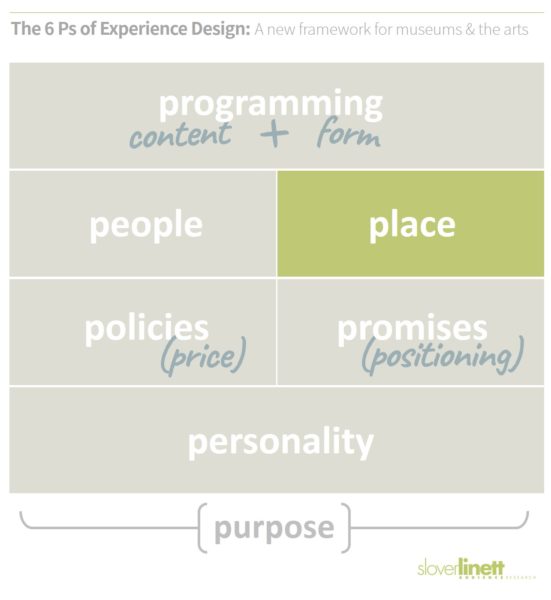

What’s place got to do with it? (6 Ps of Experience Design)

This is the fifth in a series of posts about our new framework for cultural engagement, The 6 Ps of Experience Design. If you haven’t read the preceding posts, you may want to start at the beginning.

- Introduction

- Overview of the framework

- Programming

- People

- Place [this post]

Place is another big determinant of cultural experiences, and it has two obvious components:

Geography: Where in the community does the cultural experience take place? On whose turf? How easy is it to get to, and for whom? How comfortable are different kinds of people in that place, emotionally and physically?

Geography: Where in the community does the cultural experience take place? On whose turf? How easy is it to get to, and for whom? How comfortable are different kinds of people in that place, emotionally and physically?

Setting: What’s the physical space like — the envelope for the experience? Is it outdoors or indoors? What are the conventions and connotations of the building for different kinds of people? (One person’s grand-and-elegant is another person’s authoritarian-and-antiquated.) Is it formal or informal? What kinds of experiences does it encourage — individual or social? Scripted or spontaneous? Does it authorize participation and creativity on the part of the audience, or just frame the creativity of the professionals? Does it immerse participants, transport them imaginatively to another world — or keep them within the familiar “stage set” of a cultural venue?

Those questions have received plenty of attention in the performing arts over the last decade. Theater companies and symphonies have built alternative spaces, often designed to appeal to millennials with a club vibe. Small opera companies have flourished by performing in lofts and pubs, and the rise of house concerts and networks like groupmuse have brought arts engagement back toward its nineteenth-century domestic roots (there’s a reason it was called “chamber music”). Performances “out in the community” have become more ambitious both socially and artistically, and more co-creative with those communities.

Museums have been less creative about the possibilities of place. They’ve put enormous resources into new and expanded buildings, which obviously involves a certain kind of vision and creativity. And a few have created experimental spaces within their walls. But few of these projects have involved a real rethink of what a museum does, what it feels like, or who it’s for.

That latter point — that there’s a deep relationship between place and audience — is the subject of a thoughtful 2014 report from our friends at AEA Consulting and the Irvine Foundation: Why “Where”? Because “Who”: Arts Venues, Spaces and Tradition. Noting that people of color are less likely than whites to attend purpose-built cultural facilities like performing arts centers, theaters, and museums, the report praises “shifting the scene” — that is, “bringing art to the people, rather than expecting that people come to the art”:

Work in unusual spaces capitalizes on the opportunity to create a public engaged with arts and regain the broad relevance that was once [in the early 20th century] traded for piety. … Unusual spaces can free an organization of the accumulated performance behaviors that can feel inhibitive and stifling to some patrons. In unusual spaces, silence is not a given. Socialization more often occurs during a performance event — not just before, after or at the interval. Different modes of participation are more readily welcome and authority is more often shared among an organization and its audience members. The rules around electronic recording devices are relaxed, allowing art to more readily transform into digital artifacts that can be shared through social media.

The best news, in my view, is the gradual acknowledgement in the field that the new and very different audiences who attend programs in those alternative and community spaces aren’t likely to make their way to the organization’s own venue or subscribe to mainstage series — and that’s okay. It’s not a pipeline, it’s a valid form of engagement that serves an important new constituency. One size doesn’t fit all.

Meanwhile, there’s evidence in our research that many arts institutions are fighting against their own venues — especially those that, like Lincoln Center, were built as “campuses” that isolated culture instead of weaving it into contemporary life. Increasingly, the palaces we built in the 20th century, and are often still building in the 21st, are not just irrelevant to how culture works but actually impediments to it. The audiences and communities we study tend to want intimate or at least human-scaled, informal, socially participatory, spontaneous-feeling, and welcoming cultural experiences, often with food and drink, playfulness and humor, or a personal connection with the artists, curators, or event hosts. Hard to do at a large, traditional venue. (Public libraries have been great at retooling along those lines, though.)

If you’re thinking that this all sounds more like a party than a traditional cultural offering, that’s exactly the point. We’re in a historic shift in needs and values in cultural participation, and if we want to remain relevant we need to treat place not as a given but as a strategic, creative element of experience design. In the long run, that will mean building differently. In the short run, it will mean finding, repurposing, retrofitting, activating, overcoming.

* * *

Of course, who comes to our cultural spaces and what happens in them is also a matter of the policies we set. Read the next post in the series…

Photo: A Wallcast concert at the New World’s Symphony’s innovative building in Miami Beach.