News & Notes

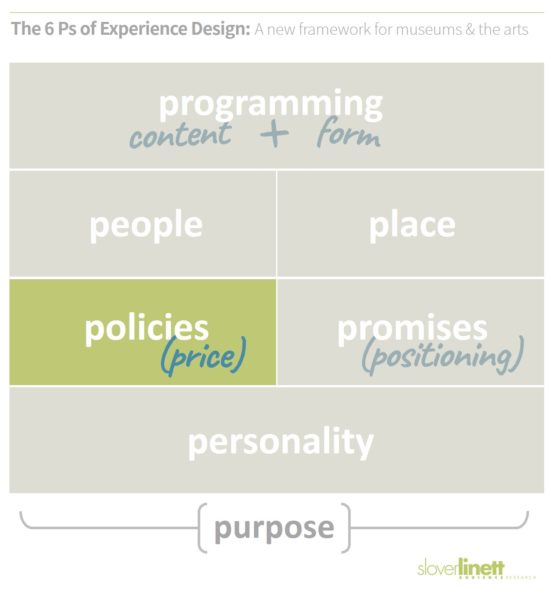

Policies for relevance (6 Ps of Experience Design)

This is the sixth in a series of posts about our new framework for cultural engagement, The 6 Ps of Experience Design. If you haven’t read the preceding posts, you may want to start at the beginning.

- Policies [this post]

- Promises

- Personality

- Bonus “P”: Purpose

What are the written and unwritten rules that shape cultural experiences? How can we use policies as a strategic instrument of experience design in museums, the arts, science engagement, and other cultural fields — a tool to deepen engagement, diversify participation, and increase relevance?

As the diagram shows, one of the fundamental policies we set is price: of general admission or those two seats in Row F, but also of membership or subscription, food and drink, merchandise, even parking and transportation. We’re often asked to study price perceptions in our audience research, and we’ve learned that for some people cost is a very real barrier to both participation (or more frequent participation) and relevance. If culture is priced as a luxury good, then by definition many people won’t want or be able to associate themselves with it.

As the diagram shows, one of the fundamental policies we set is price: of general admission or those two seats in Row F, but also of membership or subscription, food and drink, merchandise, even parking and transportation. We’re often asked to study price perceptions in our audience research, and we’ve learned that for some people cost is a very real barrier to both participation (or more frequent participation) and relevance. If culture is priced as a luxury good, then by definition many people won’t want or be able to associate themselves with it.

For others, though, perceptions of price as too high are a proxy for the value of the experience — less a “barrier” than an indicator that the “pull” of the exhibition or performance isn’t strong enough.

In the museum field, we’ve had at least two decades of debate about the virtues and viability of free admission, and a number of museums in the US and elsewhere have eliminated admission charges, with mixed results. In the performing arts there’s more at stake, since those organizations typically depend more on earned revenue than museums do. But in the last few years a number of theaters and other arts presenters have begun experimenting with pay-what-you-wish policies, money-back guarantees, and even — as part of the “radical hospitality” movement in the arts — giving away all their tickets. That last trend includes Seattle’s Intiman Theatre, whose artistic director Jen Zeyl sees free tickets as the logical conclusion of “understanding access to art as a human right,” the opposite of a luxury. Their policy is aimed not at getting “butts in seats” in general, but:

getting the butts one wants in the seats – not just the people who can afford to take the $25+ crap shoot known as a theater ticket, but the people who can’t: the woman at the corner store, the high-school sophomore, the guy asking for spare change on the sidewalk.

(This links to my point about “curating the crowd” in the people post.)

And there are myriad other policies, some actively debated and rapidly evolving, others taken for granted or considered sacrosanct. Taking photos and video in museum galleries used to be verboten; today it’s an acknowledged part of the visitor experience, and the only question is how to keep people from poking their selfie-sticks through the de Kooning. But smartphones during a concert or dance performance? Drinks in the hall or only during intermission? Tougher calls. In art museums, what about multilingual labels? Which languages? More radically, where and what can people touch?

A lot depends on how the rules are communicated. Some of our clients talk about listing the “yesses” at the entrance rather than a litany of nos.

The point is that every policy, conscious or un-, influences how the cultural experience feels and who’s comfortable participating. We need to lay them all out for consideration, experimentation, and evaluation as part of the broader work of experience design.

* * *

We’re about to pivot to the last two (or three) Ps, which are a little more intangible than programming, people, place, and policies. Before we do, I want to invite your thoughts, questions, examples, or objections. (As I’ve said, the framework is brand new and will evolve with your input). And my colleagues and I would be happy to talk with you about how to use it at your organization. Be in touch.

Read the next post in the series: promises…

Photo: Visitors playing the laser harp at Meow Wolf’s “House of Eternal Return” installation in Santa Fe. Talk about multisensory, participatory, and immersive. (You can read my review of Meow Wolf here.)