News & Notes

What the arts can learn from social work: Part 2 of a conversation with Tom O’Connor

I recently had a wide-ranging conversation with Tom O’Connor, inspired by his piece “Engaging Arts Audiences in a Time of Trauma.” In part one of our conversation, we talked about what the arts and cultural sector might learn from social work, including an embrace of systems-thinking at the leadership level and what reopening might look like for cultural organizations. In part two, below, we touch on some of the core values that arts and cultural organizations can deliver on to increase audience engagement and social relevance.

Tom O’Connor is a marketing and audience development consultant for the arts and culture industries, and the President of Tom O’Connor Consulting Group. He is also trained as a social worker and received his MSW from Fordham University in New York City, where he is based.

Tom: Belonging is at the heart of what we’re really aspiring for with relevance—providing people an opportunity to break down their sense of isolation, and culture does that in such a beautiful way at its best.

And that extends to those who work in the arts and culture, as well—a lot of people get into this field out of a sense of connection and to be a part of something themselves, and I think we should give people in our industry ways to perpetuate that. I don’t know anyone who got into this business to make people feel stupid or unwelcome or unheard.

Cory: That sense of connection is so sorely missed by audiences now, as we’re finding in the results of our national study. And I agree: I don’t think anyone in arts and culture work sets out to be a gatekeeper, but if you’re working in an established system you can kind of become that by default.

Tom: Something I say in my work all the time with marketing consulting clients is that we underestimate how important it is for people to know how much they will need to prepare for our arts experiences. A lot of people simply don’t go to things because they feel “that’s not for me because I’m not prepared for it.”

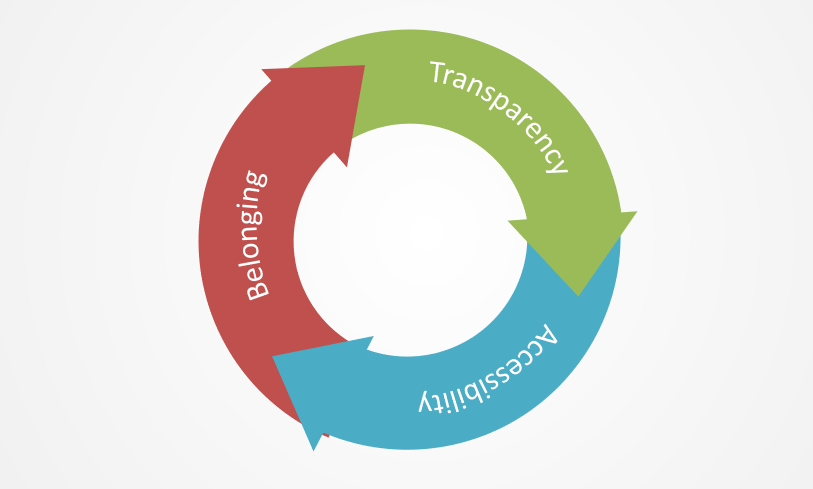

Cory: In the trauma-informed framework, one of the principles is “transparency.” And I feel like this idea of helping audiences know what to expect from an arts experience—from how to approach the content to what it might feel like to be in the space itself—is one way to provide greater transparency. Why haven’t we seen more of this, traditionally?

Tom: I think the resistance is purely about a fear that existing audience members will feel like we’re talking down to them. For example, in the classical music world, explaining how pieces are structured and what different terms mean only stands to benefit everybody. But there’s a perception that it will feel insulting to the people who are the subject matter experts in the audience. I think we give our audiences too little credit in their ability to see what we’re doing in those moments and to say: “This is being made accessible to somebody who’s new.”

Cory: Right, and: “Doing so doesn’t detract from my experience, but potentially enriches it, as well.” This kind of accessibility makes me think of universal design in web and interactive development. The idea being that enhancing accessibility for some—those who are hard of hearing or with low vision, for instance—enhances accessibility for everyone.

Tom: I totally agree. I often think about a cartoon that I’ve seen on social media. In the image, there’s a school with a group of kids waiting to go in, including a student in a wheelchair, but the front steps and the ramp are all covered in snow. As the adult in the image is shoveling the stairs, the student in the wheelchair says, “Can you shovel off the ramp?” But the person shoveling says, “I’ll get to that when I finish the stairs.” And the person using a wheelchair says, “But if you shovel the ramp we can all get in.”

Just to make this tangible in a different way: I’ve worked in New York theater for 15 years. I’ve seen hundreds of plays. And there are still certain plays—historical ones, mainly—where I don’t know what the hell is happening, because I’m just not prepared. I’m not advocating for dumbing things down, but offering a point of access for people who don’t know all of the historical context only stands to heighten the enjoyment.

Cory: And yet that onus for understanding tends to be mostly on the audience members.

Tom: Right, and to tie it back to social work concepts, I think about how we build so much connection through vulnerability, which Brené Brown talks about so beautifully in her work. An organization that allows for that vulnerability—that makes people feel that if they don’t know something it’s okay to ask—is setting a huge starting place for building a relationship with audiences. As opposed to an organization that says, “If you don’t know it’s up to you to figure it out,” which has a distancing effect.

Cory: Another way of thinking about transparency is hearing the whole story from institutions, even if there are some uncomfortable truths they have to deal with. This comes up a lot in my work when talking to audiences about museums, for instance, and wanting to hear about the provenance of objects. We’re also seeing greater transparency about the imbalance of staff versus executive pay, and about the troubling financial and political ties of Board members. How do you think institutions can build trust with their audiences when the transparency that’s fundamental to that process is exposing such ugly things?

I think there’s redemption to be had but, to me, it’s all about accountability.

Tom: This might be a little bit of a cop out, but I feel like so much of it is about an honest conversation between the power holders in organizations as to how these things that we’re talking about align with their values, and how those values have evolved over time. And then within that, what have been the trade-offs in the decisions they’ve needed to make. We need to have those conversations internally before we can confidently express anything externally.

Cory: Right. What I’m grappling with is that we’re seeing a lot of outpouring of solidarity and statements of support from institutions, but I feel like there’s a lot of skepticism about “Oh, now you’ve discovered that my community’s experienced trauma?” It’s like, nothing has really changed except that you’re saying that now you’re aware of it?

Tom: I think there’s redemption to be had but, to me, it’s all about accountability. The accountability is in naming actual quantifiable changes you are going to make. In New York City, where I live, there are a lot of organizations that are perceived as White supremacist organizations that have more of an elitist mentality to them, that have historically been predominantly White. I also know that inside of those organizations they struggle and grapple with that all the time, but they have not done a very good job of moving the needle. I think what’s been missing is a tangible, quantifiable goal for those organizations to state and then be graded on and held accountable for. I think what’s missing is a clear promise. It’s one thing to say this is how we feel, it’s another thing to say this is our promise. In many ways, it actually comes back to the case for putting systems thinkers in leadership. Because there’s a lot of really good thinking happening within organizations, a lot of good ideas and a lot of different potential paths forward that just don’t have a route toward the top of the organization. When I talk about wanting more systems thinkers as leaders, it’s really to make sure that that doesn’t continue to happen. And that we’re not necessarily thinking that it’s up to one person at the top or the people in the C suite. There’s a lot going on in organizations at every single level that can present solutions to the challenges that we’re facing right now, and so much about being a good leader is unlocking those areas to feed into one another.

Stay tuned for the final installment of Cory’s interview with Tom O’Connor, and if you still have not yet read Tom’s piece, “Engaging Arts Audiences in a Time of Trauma”, what are you waiting for?!

As always, we’d love to hear your thoughts — send us a note.