News & Notes

What I’ve been teaching (preaching?) to the next generation of museum and arts leaders

First, notice the bubble of assumptions that often circumscribes our thinking and practice in the cultural field. Then make it bigger, to let more people in.

Or just go ahead and pop the damn thing.

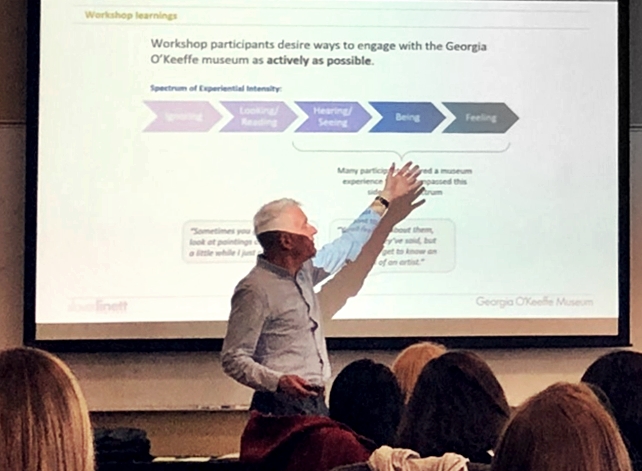

Last week I taught a half-day session on audience engagement at the Getty Leadership Institute’s NextGen program, a weeklong residency for mid-career museum professionals from the US and beyond. I tried to call their attention to the default ideas and traditional priorities that still underlie much museum practice—and also, by contrast, to the emerging ideas and progressive priorities that have begun to reshape the field.

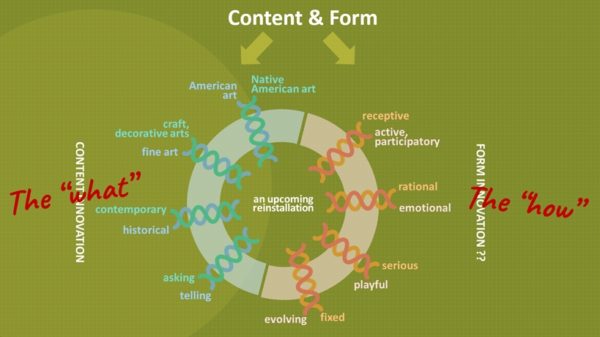

For example: Inside the bubble, museum people tend to talk about relevance in terms of content—the “what” of an exhibition or program. And for plenty of visitors (the ones right there in the bubble with us) that’s enough. They’re used to the form of a museum experience, and they accept or even cherish the cultural norms and values that that form embodies. We’ve trained them to expect that the form will remain constant as content varies.

But for others, including most of the “new audiences” and “underrepresented communities” we often talk about, it’s less than half the picture. They haven’t bought into the form—the “how” of a museum experience. So even if the content is relevant to them on one level or another, the form might not be. And even the most creative innovations on the “what” side of the equation may not be worth much to those new audiences if the “how” remains in default mode.

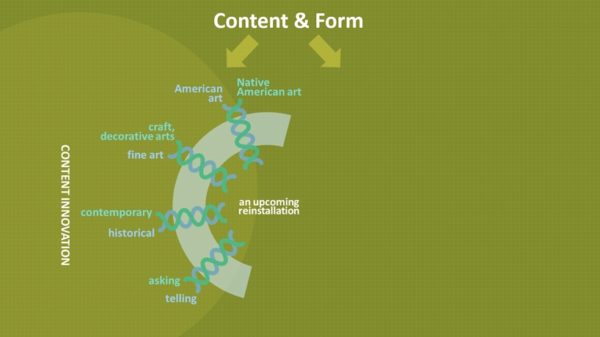

To make this concrete, I showed these diagrams from a recent proposal my colleagues and I developed for an art museum. The curators were planning a reinstallation of the American wing, and they were excited (for good reason) about some of the creative risks they were taking on the content side: combining historical and contemporary objects, for example, and displaying Native American art alongside “American” art for the first time.

But they and their colleagues in the education and evaluation department didn’t seem to be thinking much about the form side, which we suggested is equally important. (We weren’t suggesting particular innovations on that side, just raising some corresponding questions about the “how.”)

The point is, if museums offer “experiences,” as the whole field has acknowledged, then we need to accept that we’re in the business of experience design, which includes but is not reducible to content. In addition to the “what,” we need to think hard about how our visitors need to experience that content, how they want to connect to it (and to each other). And that’s not all: we also need to think about the “why,” the “where”—the space and what it connotes and authorizes—and especially the “who.”

Once you notice this particular assumption in the bubble, you start to hear familiar museum rhetoric differently. Take the way we think about equity, inclusion, and representation. The problem, we often hear, is that people of color and non-European immigrants “don’t see their cultures represented in our collection.” The implication is that if the objects on display—the content—become more diverse and representative, so will the audience. But since experience design is much more than just content, and since the very notion of a museum is a European cultural form, that’s not likely to be enough. What we ought to start saying is, “They don’t see their cultures represented in our experience design.”

Which is harder to fix, but not impossible. (Hint: We also talked about the role of audience research in revealing, then expanding, the bubble.)

I don’t mean to pick on museums; every field of culture has its bubble. I used the same metaphor a month ago when talking with theater management grad students at the Yale School of Drama. Look, we all work within the bubble sometimes; the current business model needs to be supported and successful in order for cultural organizations to take new risks, test new ideas. But sometimes we need to work against it. And that starts with seeing it, in all its shimmering, fragile strangeness.

What’s in your bubble—and what’s outside of it? Shoot me a note.

Special thanks to Toni Guglielmo, Melody Kanschat, and Chris Hosch at Getty Leadership Institute for inviting me to share my thoughts with an awesome group of NextGen Fellows.