News & Notes

Taking a stand is a tradeoff, but a smart one

Talk less! Smile more…

Don’t let them know what you’re against

or what you’re for.

— Burr

I’d rather be divisive

than indecisive…

I am not throwing away my shot.

— Hamilton

Like a lot of us, I’ve been thinking lately about advocacy and change, inspired most recently by the millions of people in 185 countries who participated in the youth-led Climate Strike last week. Many natural history museums and science centers, including clients of ours like the Field Museum and Museum of Science Boston, threw their institutional support behind the protesters, which made me feel a bit better about being at my desk that day instead of on the barricades.

But many didn’t, and I’ve been imagining the conversations that must’ve taken place in those conference rooms and directors’ offices.

We study. We describe. We don’t advocate. We’re about the science, not the politics.

Which is why people trust us. We can’t afford to squander that.

At least, that’s what we used to hear, until very recently. That last part, about people trusting museums, may well be true. And museum professionals have been particularly proud of that, even sometimes defensive about it — as if trust were synonymous with overall value and success.

But it isn’t. Being viewed as trustworthy isn’t the same thing as being relevant. And as more museums and other kinds of cultural institutions begin to tentatively or energetically shed their institutional objectivity and join the messy world of action and progress, I’m beginning to think the two may be inversely proportional.

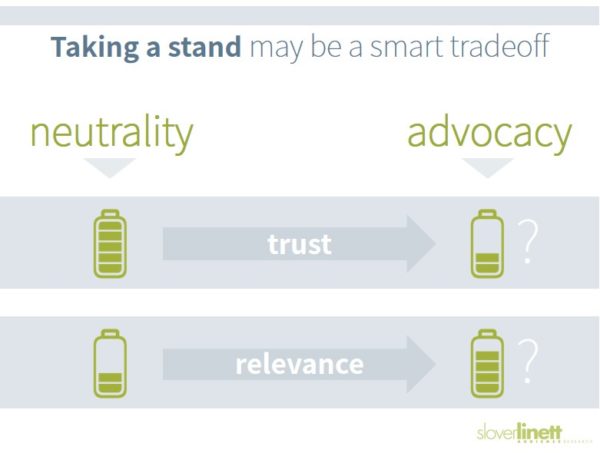

That hypothesis is illustrated in the diagram (click to expand or print). The default institutional stance, at least at most STEM museums and other cultural institutions, was neutrality. After all, 501(c)(3) nonprofits aren’t allowed to get too political, and the boards and city agencies that control most museums weren’t comfortable wading into anything that smelled like controversy. That emphasis on objectivity earned public trust, sure. But it also kept those institutions from being part of — from mattering in — the conversations and, yes, the fights where the real energy is.

Fetishizing trust (or at least the kind of trust premised on neutrality and objectivity) kept many museums above the fray but also off to the side. We earned trust at the price of relevance.

On the right side of this hypothesis-diagram, the opposite holds: By worrying less about trust, by taking a stand, we can earn greater relevance, centrality, even urgency. We don’t have to just describe or present; we can get in there and risk really mattering.

This has been the animating realization and exhortation of the Museums are Not Neutral movement, right? And I think it’s what many natural history museum and science center leaders have begun to acknowledge in the last few years: that climate science isn’t going to save us — we also need climate action.

It’s the “Hamilton” argument, quoted selectively above. At a pivotal historical moment, would you rather be Burr or Hamilton? The museum field must not throw away its shot.

Ditto other kinds of cultural institutions; this isn’t just about science or climate. The same tradeoff may apply to art museums, symphonies and theaters, libraries, community festivals, the whole gamut. Neutral goals like “being a gathering space for discussion” or “letting people decide for themselves,” are giving way to more activist sensibilities and language. Institutional subjectivity is becoming a thing.

Will there be critics and defectors? Will science and culture institutions lose ground with some visitor and supporter segments as their neutrality comes into question? Probably. But the upside may be far more valuable, both for these institutions and the communities and society they serve. I do empathize with the challenges this idea poses to, say, a planetary scientist who works at a natural history museum and needs to get her research published. She can’t afford to blur the lines between empiricism and advocacy. But her institution can’t afford not to.

What’s your institutional stance, and is it shifting? I’d love to hear about the conversations you and your colleagues and trustees are having, plus any thoughts about this diagram. Like any hypothesis, it needs to be tested; we’re eager to do more social research on these questions. Any takers?