News & Notes

What the arts can learn from social work: Part 3 of a conversation with Tom O’Connor

This is the third and final installment of my conversation with Tom O’Connor, a conversation inspired by his piece “Engaging Arts Audiences in a Time of Trauma.” In the previous excerpt, we left off talking about the benefits of having systems-thinking leadership during times of change and, as Tom put it, potential redemption for a field that is coming to terms with its own complicity in longstanding systemic inequities. Below, we discuss what it might look like for organizations to truly be more community-centric, and how to mitigate the toll it will likely take on arts workers for them to administer the kind of care needed going forward.

Tom O’Connor is a marketing and audience development consultant for the arts and culture industries, and the President of Tom O’Connor Consulting Group. He is also trained as a social worker and received his MSW from Fordham University in New York City, where he is based.

Cory: Even before this moment of multiple crises, many of the institutions I work with have been talking about shifting their focus to be more community-centric places where this kind of urgent and even uncomfortable dialogue can happen. My concern is that the brunt of this community-facing work will be carried out by front-line staff, who are already being asked to do a lot, often for not very much pay. And now we’re putting on top of that the kind of trauma-informed work that a social worker might be doing. It’s really deep, heavy labor we’re going to be asking people to do, and I really am concerned that it’s asking too much.

Tom: I would hope that any leader of an organization that is tasking their front line or specific departments with this type of work is putting their money where their mouth is in terms of training and professional development. And there are a lot of resources for this kind of training through the National Alliance of Social Workers, for example. But I also want to grab onto one word that you said, which is so apt: you said a “shift” to a community centered or community driven perspective, and I want leaders to spend a lot of time with that word “shift.” I want them to think about what we are shifting from, and why we are where we are in the first place. And if they can demonstrate that they’re working to understand and ameliorate whatever that original state is, I think that a lot of the work that’s being asked of front-line or junior staff will feel like it’s coming from a full sense of integration with an organizational vision and a mission. If you’re not changing anything at the top and maybe doing one or two more plays by Black playwrights every season or two [in the case of a theatre], and not doing a lot of high-level interrogation of your organization, it’s going to be really hard to ask those junior staff to lead a change from the bottom up.

Cory: At the risk of being overly pessimistic…workers in the arts are already subject to pretty high burnout rates. And the same is true, from what I understand, of social workers. So, putting those together, it seems superhuman to try and ask people to provide both arts administration and this level of community care. So as workers in the arts, how do we do the right things for our audiences, ask the right and challenging questions, support our communities in thoughtful ways, but then also look out for our own health and well-being at the same time?

Tom: I want to come at this first from being an arts marketing consultant and then I’ll come at it from being trained as a social worker. As an arts marketing consultant one of the things I say most often is that doing everything is not a strategy. There are a million different tools and a million different things that we could be doing to quote unquote reach people, but if they’re not in alignment with a larger strategy they’re just a waste of time and energy. So when we are thinking about shifting to new models and ways of thinking and being in our communities, we need to have an honest conversation about what we can stop doing, about what things we are doing that are not serving those larger goals and can just go away to make bandwidth.

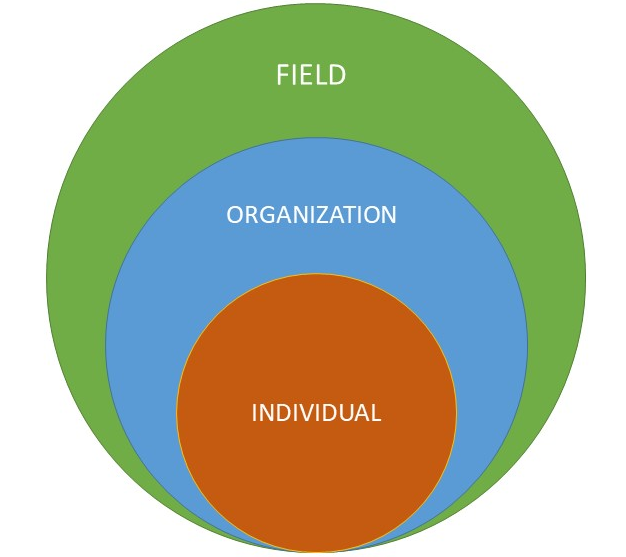

On the social work side of things, the burnout often comes from the enormous caseloads that people are carrying, and the lack of dedicated time to process and heal from vicarious or secondary trauma. There’s an expression that we should “give from our abundance, not from our core,” otherwise we cannot give for too long. So when people are overworked and underfunded, which is often the root of the problem, that can’t be sustainable without sacrificing from their core. And I think that’s an important thing to remember. The way to prevent that comes back to the systems approach. At the micro level: What are the needs of individuals to carry out that work? At the mezzo level: What are the organizational needs to make sure resources are available to make that work meaningful, sustainable, and integrated? And at the macro level: What are the resources needed for our field to prioritize this work and create structures and networks, wherein people can get ongoing support from their colleagues? In that latter category, I think most about funding and stated funder priorities.

When people are dealing with their own sense of burnout, there’s a need to just create space to talk about it and process it, which is a lot of what trauma-informed care is about, too. Anybody who’s feeling like: “I can’t meet the needs of this job” or “I can’t do enough, I can’t make a difference,” that’s not only self-defeating in terms of their energy and their fatigue but it develops into a sense of shame of not being able to carry out their function in what they think they’re supposed to be doing. And that leads to more disconnection, isolation, all of that. Whereas if you can actually create ways to connect with people who are also doing that work—whether they’re in your own organization or in another organization—to create feedback loops, to create systems of support, to create resource sharing, that’s the way to do it.

But, realistically, so much of it is about funding and expectations. So many of these organizations in which people are experiencing burnout, it’s because they’re expecting people to handle a workload of twice a reasonable human level. We need to be conscious of that and I don’t think there’s any level of emotional support that can resolve just a completely overburdened human being.

Cory: I would love to hear about some of the reactions to your piece and what people are telling you they’re planning on doing going forward.

Tom: We’ve had several thousand people read this piece and I heard from so many about how it resonated with them. If I had to summarize the feedback I’m getting, it’s that they’re grateful to place the work that we do in the field back in the human context of why we do it.

Whenever you’re talking about an idea that’s bridging different areas, it can be hard for people to see the direct application of how they can take that and run with it. And I’ve had some really interesting initial conversations with people about how they are taking these constructs and just asking within their organizations: “What is our feeling on these six principles and how do we feel like we are addressing them?” I do think there’s a little more work to be done, and we’ve actually developed workshops around this, to help facilitate those conversations and make that connection between the ideal and the realities of what’s going on at these organizations.

Cory: Are there some practical guides out there for folks if they’re thinking about how to turn from this framework to something that is more tactical?

Tom: Yes, that is something that we’re working on: how we can apply this framework in practice. I suspect this will come once we have conducted more workshops. I do think a lot of this work is so specific to individual communities and to what they’re going through. One of the six principles of trauma-informed care that I referenced in the article deals with “cultural, historical, and gender issues,” and thinking about how that plays into trauma that people have experienced. The way that happens in predominantly White communities versus communities like my own which are extremely diverse—those kinds of conversations are going to look really different.

But that connection won’t happen if people don’t feel like a space is for them—a space where they can let down their guard and feel welcome, but also feel that this place genuinely cares for them in this moment.

Cory: Right, and there’s often generational trauma on top of personal trauma. So I would imagine that the goal can’t be to completely heal trauma necessarily—that seems like a bridge too far. But what should the goal be?

Tom: I’m really glad you asked that because I’ve had some people who think I’m proposing that arts organizations need to become these workshops of trauma healing. I think we provide some of the building blocks for that, but I’m not proposing that we try to fulfill that role in our society. Trauma-informed care is not just the idea that because you put these six principles in place, trauma is healed. The idea is that it’s not perpetuated, that it’s not exponentially worsening in the person and that we are providing a space in which they feel that they can get some of the help they need. And to do so by connecting—with the art and with other people. But that connection won’t happen if people don’t feel like a space is for them—a space where they can let down their guard and feel welcome, but also feel that this place genuinely cares for them in this moment.The things I’m putting forward are ways for us to increase our ability to show people that sense of care, and to involve them in the process of making us better as organizations.

Cory: “Collaboration” is one of the principles in the framework, and discussions on equity often center around questions of power dynamics and power sharing. Any thoughts on what power sharing can look like between an organization and the communities it serves?

Tom: I think that “listening” is a small word with a huge meaning that a lot of organizations need to do a lot of work on. And there’s a difference between listening to validate what we’re already doing versus listening to actually impact change and to honestly answer a question we have. For example, how might we engage our audiences to serve as our advisors and ambassadors for how to build confidence in coming back to us post Covid? That’s not to say that we give every stakeholder the keys to the kingdom and say it’s up to you. But it’s better than the alternative thinking which is: we should be able to figure this out ourselves and then we’ll roll it out and cross our fingers and hope that people don’t attack it. Which is the approach that I believe a lot of organizations feel beholden to take. I won’t say they’re afraid of collaboration, I don’t really think that’s true. But I think they’re afraid of the vulnerability, of being seen as not having all the answers. And, again, I also want them to look at the strengths that they have within their organization, and think about ways to really unleash those strengths and bring them to the fore.

We hope you benefited from the final installment of Cory’s interview with Tom O’Connor. The first part can be read here, followed by Part 2, and we cannot recommend enough Tom’s piece, “Engaging Arts Audiences in a Time of Trauma”.

We’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas — send us a note.