News & Notes

“Out of turmoil comes newness”

It is all around us. Some see it in the soft twisting branches of a plant they started growing during the pandemic, some in the goosebumps their daughter’s singing gives them, some in the witty banter they have with their family as they cook a holiday dinner together or in the faces of people taking in paintings at an art museum. Regardless of how, when or where, art (and creativity) is everywhere, and it is limitless.

In fact, these were all examples given by the participants in a research study my colleagues Ciara C. Knight, Tanya Treptow, Camila Guerrero and I conducted this year — the qualitative phase of Culture + Community in a Time of Transformation: A Special Edition of Culture Track. For the study, we interviewed fifty Black people around the U.S. to explore the role of art, culture and community played in their lives, especially during the pandemic.

As the interviews started, we were almost a full year into the pandemic and social isolation (at least in the physical sense). In this isolated state, we were also being bombarded with news about Covid-19 deaths, the US election and its aftermath, and the televised and graphically described murders of Black people. With all this collective trauma hanging over our heads, we as Black people still found some solace in moments that brought us joy, connection, care, comfort, safety, belonging and trust, all of which we explored together in these interviews. Our conversations revealed that these moments were not just lifelines, but also reminders of the possibility of a new world. As one of our participants described, “out of turmoil comes newness.”

When I started this project, I was a researcher with over a decade of experience in human social behavior but had been working in the cultural sector for less than a year. Every field and sector have their own histories and assumptions. It was eye-opening to explore and navigate the arts and culture sector’s assumptions through the eyes and experiences of our participants. There was so much that people loved, valued and appreciated about arts and culture, but also so much more to be achieved, reimagined and, in some cases, dismantled. So how and where to start? Our conversations revealed a pressing need to rethink many of the ideas in the field about how Black people connect to art, culture and community.

Here are a few questions our findings raised that might inspire some of this rethinking:

- Rethinking connections to art and creativity. As in the examples I mentioned at the beginning of this post, people see art and creativity everywhere. It’s all-encompassing. Everybody we spoke with created art themselves and/or connected to it on a deep and personal level, and they also used art to connect to others. Art had great relevance to people’s lives. So why are the sector-wide questions that focus on Black people’s participation in “traditional” arts spaces place so much emphasis on relevance, if relevance is already there?

- Rethinking representation. In these conversations, we also heard about representation and what it means. Authentic and holistic representations were key. Seeing all Black stories represented, as opposed to just trauma stories and those that promote “respectable” Blackness, and seeing Black minds and opinions valued and celebrated, were cues of authenticity. So why is there so much focus on trauma stories and respectability politics? Who benefits from this kind of representation and who doesn’t?

- Rethinking self-care and personal wellness. This was an interesting topic to explore because, in our conversations, the participants talked about themselves as well as their own assumptions about other Black people. The majority described therapy and mental healthcare being a taboo in the Black community, yet a lot of them were actually using therapy and therapeutic approaches to care for themselves and stay healthy and balanced. So where are our own assumptions about caring for our minds and bodies somehow being unacceptable coming from?

- Rethinking belonging. Belonging was described as a deeply personal feeling, one that could be found in any space or experience that let people be their authentic selves. There was a shared sentiment that all people belong, anywhere and everywhere. Any space that was welcoming, safe, and comfortable was a space where people could explore and express their authentic selves. So where are the questions about whether Black people feel belonging in certain spaces coming from? Why don’t we focus on whether these spaces are welcoming enough to help people express their authentic selves?

- Rethinking trust and trustworthiness. When it came to cultural and community spaces and organizations, we talked more about trustworthiness than trust. Trust was defined as dependent on trustworthiness, which needed to be earned through consistent action. So why is the focus on whether Black people trust instead of whether the organizations or spaces that want to be trusted are actually trustworthy?

Our new report explores all these concepts to help us rethink and reimagine. I hope that it leaves readers with a sense of shared humanity, connection, and enthusiasm for new possibilities—but also with new questions. After all, sometimes it takes a different question to open the door to new beginnings…

In the following months, my colleagues and I hope to share further reflections about the study and our findings, and host conversations to continue and further the dialogue about this rethinking process. For any questions and comments, please do not hesitate to reach out to me.

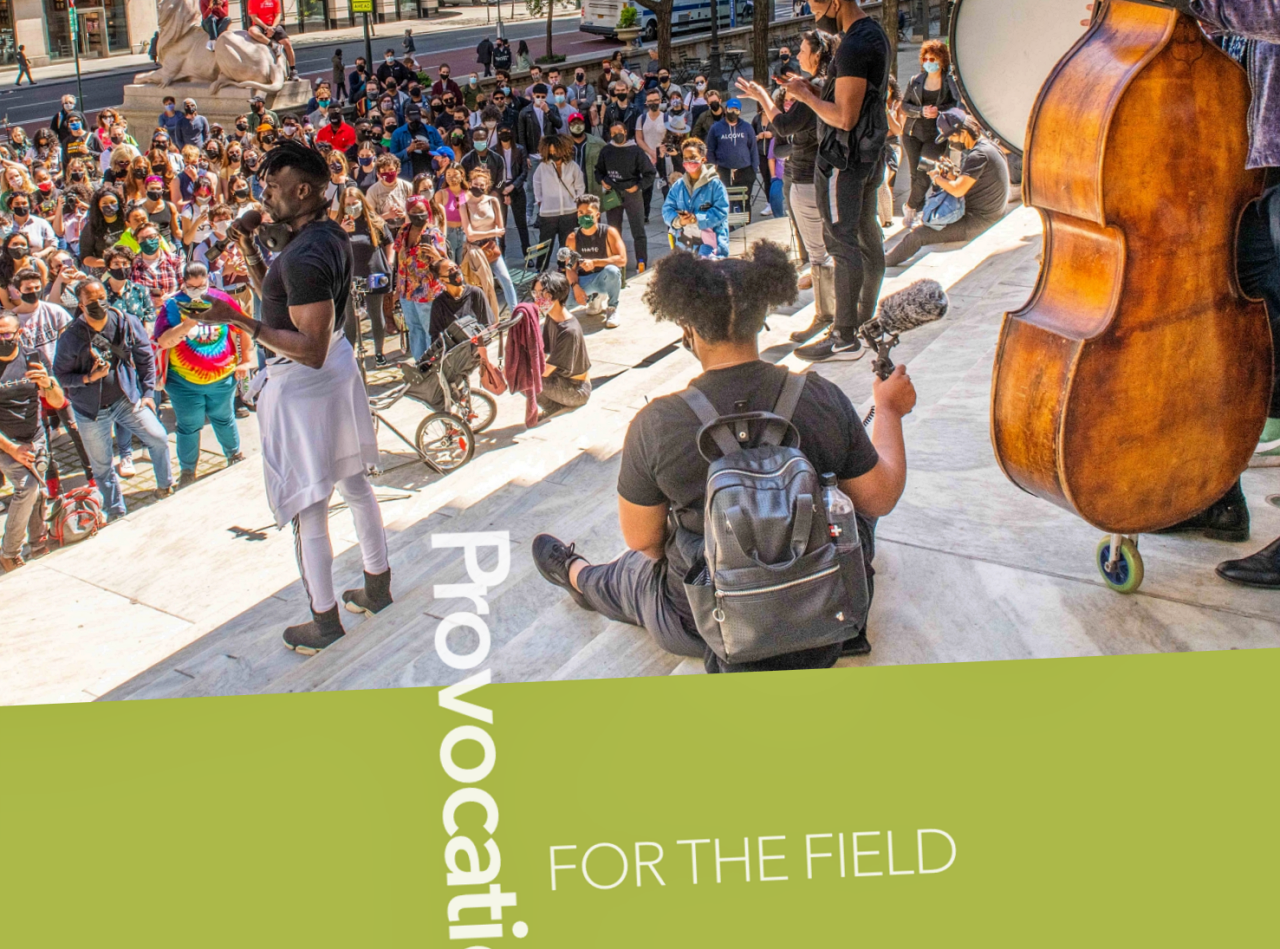

Photo at top: Detail from the new report, titled “A Place to Be Heard, A Space to Feel Held: Black Perspectives on Creativity, Trustworthiness, Welcome and Well-Being.” The image glimpsed here was generously provided by NYC-based photographer Deb Fong (debfong.com, IG @deb_fong_photography) and was taken in May 2021 at Broadway United for Racial Justice, an action hosted by Unite NY. The event began on the steps of the New York Public Library, where organizers and speakers Rodrick Covington and Clive Destiny, accompanied by musicians including Russell Hall, led this creative community of artists and supporters in taking a firm stand together against racism. View the report for the full image and other images by Deb.